The prophet is a realist of distances, and it is this kind of realism that you find in the best modern instances of the grotesque.

—Flannery O’Connor, Mystery and Manners

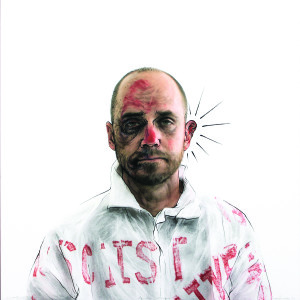

SOME MONTHS AGO, while traveling, I walked full-force into the sloping ceiling of the unfamiliar guest room where I was staying. The blow to my head was so sudden and solid that I fell like a stone. Though momentarily stunned, I rose from the carpeted floor unharmed save for a small lump on my head. Had friend and artist Scott Kolbo witnessed my self-inflicted pratfall (which he did not), I feel certain that he would have found my mishap hilarious. In his mind’s eye there would have appeared the crazy image of some dazed comic character with an aureole of stars and other odd symbols spinning about his head [see Plate 1]. I do not mean to suggest that Scott would wish harm to befall me or anyone else. Quite the contrary. But it is these kinds of dumb moments—the manifold clumsiness, bad decisions, and calamities that showcase the darker side of our humanity—that animate this artist’s work.

Introducing Kolbo in this manner might cause you, my reader, to suspect that he is not your kind of guy. But you would be wrong. I first met Scott in the late 1990s when he was an entering MFA student at the University of Wisconsin. Then, as now, he possessed a wry wit and a deep Christian faith. Paired with these qualities was an abiding skepticism—less an artist’s edgy critique of our messed-up world and its flailing institutions than a suspicion of the limits of his own talent, understanding, and character. If, like me, you weary of the narcissism that characterizes so many contemporary artists, his self-effacing, gee-whiz manner is refreshing. But don’t be fooled: since 2000, Kolbo has had twenty-four one or two-person exhibits. With a smattering of ballpoint pens, Prismacolor pencils, charcoal, and printer toner close at hand, Scott excels as a draughtsman, and from handmade to demanding digital formats, he is a skilled printmaker.

PLATE 2. Scott Kolbo. Jeremiah Preaching 9, 2001. Inkjet and mixed media on paper. 11 x 8½ inches.

An early work given to me by Scott is a multi-fold lithograph that features the preacher Jeremiah, a recurring figure in his work [see Plate 2]. The print unfolds from left to right so that, frame by frame, the preacher is metamorphosed from a man to a jackass. Like a rabid evangelist battling for “truth” on a university mall, Jeremiah condemns and exhorts. Notably, this middle-aged, balding, Bible-thumper—dressed in a white shirt, striped tie, and checked slacks—is shoeless. He is neither a mega-church pastor nor a slick TV preacher but a mere court jester, a mediocre standup, a frustrated fundamentalist. He is one crying in the dystopian American wilderness, but no one listens.

Witnessing the sad absurdity of Jeremiah’s situation, we can, with Kolbo’s help, observe that the whole setup is pretty funny. Or is it? If we give Kolbo’s visual narrative a bit of room to elbow in, our sense of smug superiority may be short-lived. To be sure, most of us would be disinclined to pursue Jeremiah’s apparently fruitless calling. He, alongside other prophets, preachers, and evangelists of his ilk, is given to a particular kind of work—to proclaim the word of God, to share bad news, to announce judgment. At least that is Kolbo’s take. And famously, prophets (like Jonah) run from God, preachers are given to moral misdeeds, and evangelists believe that they have the power to save. But what if something of Jeremiah resides in each of us? In seeking to speak truth or even to meet the simplest obligations, are we not also vulnerable, misguided, and ignorant? What of our odd proclivities, addictions, and unfortunate choices? Perhaps, like all the rest, Jeremiah is doing the best he can to live beneath Adam’s curse.

PLATE 3. Scott Kolbo. Heavy Man Grotesque, 2008. Ink and charcoal on paper. 19 x 11 inches.

Those who know Scott will, I suspect, observe that Jeremiah resembles the artist. So also does Heavy Man, another of his creations. Like me, Heavy Man could stand to shed a pound or two. As he descends a stairway, its risers give way, and he seems to be forever falling through floors and crashing through ceilings [see Plate 3]. Of course the entropy of the material world is the partial cause of Heavy Man’s worry—rickety stairways do collapse, houses are set ablaze, and acts of God disrupt. Besetting social problems—the swelling ranks of the unemployed, the abandonment of the center city in an old manufacturing town, the degradation of pristine skies and streams—may also account for his troubled mien. Heavy Man’s true burden, however, is not his flabby, untoned corporeality; rather it is the unbearable weight of being. To put it in mid-twentieth-century language, he is overcome with existential angst.

The domain that supports Kolbo’s characters is inelegant and unrefined. It is home to weed-covered lots, junkyard dogs, seedy carnival midways, and lumpy-figured women. In his prints and drawings even a child’s balloon can wear a sad face. Alas, in Kolbo’s world, everything has run amok. Jeremiah and Heavy Man, alongside Kolbo’s other personalities, exist in it as buffoons, asses, fools, thugs, and victims trapped in the dull, sometimes deadly, whorl of their banality. But if Heavy Man seems resigned to these conditions, then Jeremiah rails against them. Taking a step back from particular works to get the larger view, a bipolar oscillation occurs between Heavy Man and Jeremiah, and amid this, traces of the artist’s persona are exposed.

Classically, there have been two primary artistic responses to the clamor, squalor, and tragedy of what we commonly term the “human condition.” The first is aspirational. This type of art invites us to “set our mind on things above,” to seek transcendence. Though he is a man of faith, this is decidedly not Kolbo’s artistic direction. Rather, he has chosen a second route: to investigate the comic and the grotesque. Though he is neither a writer nor a southerner, it should be no surprise that Flannery O’Connor’s fiction eggs him on. In fact, some of his early work sought to interpret stories such as “Good Country People” directly. In her essay “The Grotesque in Southern Fiction” O’Connor writes:

It’s not necessary to point out that the look of this fiction is going to be wild, that it is almost of necessity going to be violent and comic, because of the discrepancies that it seeks to combine…. Even though the writer who produces grotesque fiction may not consider his characters anymore freakish than ordinary fallen man usually is, his audience is going to; and it is going to ask him—or more often, tell him—why he has chosen to bring such maimed souls to life.

“Freakish” and “maimed,” Kolbo’s characters belong to the genre O’Connor describes, and his oeuvre is rightly classed alongside graphic novels, political cartoons, and even comic books. While he relishes these kinds of associations, his work pays homage to a deeper history. Here the weird Chicago School and especially Jim Nutt, the countercultural antics of R. Crumb, the more sublime paintings and drawings of William T. Wiley, and the contemporary work of South African artist William Kentridge all come to mind. So also do the social protests of the late-eighteenth-century Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco de Goya and the cartoons of the nineteenth-century French satirist Honoré Daumier.

Further back, Kolbo’s visual forms bear substantial affinity to the work of northern Renaissance masters like Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and Jan Steen—each of whom found rich pictorial material in the unabashed profanity and earthiness of the peasant class. Art historian Lisa DeBoer points out that this Netherlandish tradition highlights “the ‘droll,’ ‘witty,’ and ‘farcical.’” She goes on to argue for the importance of sustaining the figurative tradition in western art: “Even after the collapse of the Modernist consensus in the 1960s and 1970s, there has been surprisingly little room in the critical mainstream for a non-ironic, warmly human, not to mention figural, vein in art.” DeBoer posits, “It is an interesting challenge to consider which twentieth-century artists might offer a comic vision of humanity in their art.” It seems to me that Kolbo—the most sincere ironist I know—meets this challenge.

Like O’Connor and her characters, countless painters, philosophers, historians, pop-culture gurus, preachers, and poets have directed prodigious effort to sort out the whys and wherefores of our falleness, but none more presciently than the apostle Paul:

So I find it to be a law that when I want to do what is good, evil lies close at hand. For I delight in the law of God in my inmost self, but I see in my members another law at war with the law of my mind, making me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members. Wretched man that I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death? (Romans 7:21-24)

Christian believers or not, most hearers will recognize more than a little of the yawning gap that Paul describes—the chasm separating the grievous limits of our human nature from what we call, more optimistically, our human potential. Whatever hope this potential summons, we know all too well that it must be weighed against the reality of our terminal condition. The Bible (and most of the orthodox theological scaffolding that it supports) simply terms this, our malady, sin. For some time it has been considered impolite, and now impolitic, to speak of this. I take it that this is because the mention of sin leaves folks feeling bad, even ashamed. Worse still, claims concerning right and wrong invite moral judgment which, in turn, signals the presence of moral standards, and this presumes absolutes. Whatever view you may hold of these matters, the struggle surrounding our human condition is central to Kolbo’s project.

PLATE 4. Scott Kolbo and Lance Sinnema. Escalation Battle 01, 2012. Archival inkjet, ink, Prismacolor, and charcoal. 22 x 30 inches.

His work is not limited to two-dimensional prints and drawings, nor is it solely given to explorations of the self. In recent years he has experimented with animation and also staged some zany performances. The curmudgeon in me wearies of performance art, stranded as it so often is between conventional art making and excellent theater or film. But viewing the final iteration of Kolbo’s Escalation (seen by me only in video) was great fun. Consider the absurdity of two artists dressed in white suits and shirts and wielding foam clubs that have been saturated either in red or blue printer’s ink doing battle with each other [see Plate 4]. In a series of ten two-minute rounds and with mocking fierceness, these combatants stamp red and blue slogans like “racist” and “socialist” on the tabula rasa of the other’s uniform. This particular work, performed in the summer of 2013 on a grassy urban field outside the Anchor Art Space in Anacortes, Washington, was the second of two “live battles” staged by Kolbo and artist collaborator Lance Sinnema.

The apparent purpose of Kolbo and Sinnema’s staged to-ing and fro-ing, their phony jabbing and clubbing, is to advance their respective brands, red or blue. And it turns out that their “dumb method”—cheesy props, low fidelity sound, and amateur videography—is well-paired with their “dumb message.” The inky mess that emerges is reminiscent of Yves Klein’s 1960 performance pieces wherein he pulled nude female models through blue paint spread on the floor and then used their inked-up bodies to print monochrome images on large blank canvases. I suppose that Klein’s effort (which strikes me as awkwardly misogynistic) was innovative, but its legacy is mostly the trademarked color known to us now as International Klein Blue (IKB).

Kolbo and Sinnema’s Escalation could seem equally pointless. After all, save for the opportunity to draw a small gathering and make some art, these artists do not accomplish very much. In fact, Escalation turns out to be a very clever forum for these artists to register their complaint regarding what they describe as “the increasingly volatile language that surrounds our current political discourse.” Dear reader, keep me from connecting the dots for you as we wait, with bated breath, to see whether blue will dominate red or red will be outdone by blue.

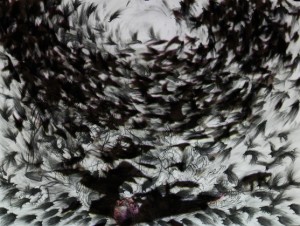

PLATE 5. Scott Kolbo. Sonic Medicine: Jeremiah (image sequence detail), 2013. Video projection, ink, and charcoal. 42 x 57 inches.

Early in 2010 and predating Escalation, Kolbo began to explore a new theme he called Sonic Medicine. Prior to this he had been investigating the response of his characters to pestilence, sketching hordes of attacking insects. Concerning his new direction, Kolbo comments, “I thought it might be a good idea to introduce some ‘birds’ that could have a more positive effect. I was drawn to the idea of singing that might ‘soothe the savage beast,’ and so I tried to imagine what these bird-creatures would do to Jeremiah.” The resulting work consisted of video clips and drawing sequences that depicted flocks of birds alternately attacking and singing to Jeremiah [see Plate 5]. It seemed to Kolbo that before the preacher could be soothed in any way, he would first need to be “knocked down and shut up.” While the birds in Sonic Medicine are something less than the ravens sent by God to deliver meat and bread to Elisha in the wilderness east of the Jordon, neither are they the menacing predators of Alfred Hitchcock.

Given the wacky yet prophetic nature of Kolbo’s comic world, a brief aside concerning our late postmodern moment seems warranted. Logged, tuned, or dialed in, our increasingly digital world is training us to consume the sound, images, and text that stream toward us. We have learned to fill our apparently empty hours with this nonmaterial spectacle—one that appears to us as an unending admixture of unremarkable postings, comments, and images that are shot through with vivid, though random, instances of wonder. These brilliant moments are so dazzling that we willingly sift through the residual flotsam and jetsam as if panning for digital gold. If you or someone you know spends countless hours on Facebook, watches sports around the clock, or plays video games to the exclusion of all else, then you have experienced—or are at least a witness to—this reality. While this spectacle is surely not all cultural pap, it tends to belittle history and routinely sidesteps the prospect of meaning. But so long as our “disbelief” remains “suspended,” it no longer seems needful to speak of things as if they should or even could cohere.

With this as background, it seems to me Jeff Koons is the quintessential postmodern icon maker. He lends physical form to the nonmaterial spectacle that I have described. On November 12, 2013, the artist’s Balloon Dog (Orange) sold for over 58 million dollars at Christie’s in New York. Though sensational in appearance, this stainless-steel sculpture—standing more that twelve feet high and meticulously crafted by Koons’s small army of assistants—is spectacle without substance, a magnificent nothing. How can it be that Koons’s work is thought to possess such value? The art market simply declares it to be so. Meanwhile, few seem troubled that Balloon Dog (Orange) has little bearing on our humanity and no real purchase on the larger world of ideas.

Kolbo’s work (a fair bit of which involves digital media) is a counterproposal to all of this. I suspect that Kolbo would find Koons’s dopey balloon dog, the lavish care and expense required to craft it, and its absurd overvaluation really funny. Enter irony. As a rhetorical device, artists like Kolbo employ irony to reveal contradiction, summon a sardonic smile, challenge the status quo, and mock power. In a healthy democracy these are vital functions, though they can easily fall prey to cynicism. But not in Kolbo’s hands. For him, irony is a comic means to probe the gap between the dumb condition and divine dignity of his characters. Threaded throughout his sleight of hand, jokiness, and tomfoolery is the conviction that human persons, no matter what their situation, mean something. As with O’Connor, the humane exists within the profane.

Having considered but a few of Kolbo’s works, what then shall we make of his larger project? Let me suggest three responses. First, along with theologian Cornelius Plantinga, most of us can agree that this world is “not the way that it’s supposed to be.” Scott’s drawings, prints, performances, and animations remind us (in case we had forgotten) that life’s conditions and events can seem almost unbearable. We are awash in internal disquiet and surrounded by misfortune and squalor.

Second, in his exegesis of first-world dumbness, sorrow, and injustice, Kolbo sounds a prophetic voice: our stupid, though often benign, neglect—of the natural world, our institutions, our neighbors, and even of those we profess to love—rests at the center of much of our crisis. In brief, though we do possess considerable agency in the world, we are prone to squander it.

Third, in responding to Kolbo’s work, some may turn to embrace the spiritual discipline of lament. In the short view, humor—the kind of resigned laughter that sometimes accompanies despair—does offer momentary and often needful release. But a more substantial salve is the language of lament, and here the Judeo-Christian tradition is not silent. From Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden, to the plagues leveled against Egypt, to Israel’s long sojourn in the wilderness, to the Passion of Christ, Scripture speaks of our afflictions with candor and addresses our suffering forthrightly. Amid all of this, hope is never extinguished.

As much as any, the words of English hymn writer Isaac Watts—usually associated with Christmas, but written to celebrate Christ’s second coming—offer an apt conclusion:

No more let sins and sorrows grow,

Nor thorns infest the ground;

He comes to make

His blessings flow

Far as the curse is found….

One day Adam’s curse will be overwhelmed by joy. On that Day, suffering shall cease and blessings flow. Meanwhile, the discipline of lament can lead us through darker, more confusing times. It is this invitation to lament that occupies the heart of Kolbo’s creative project.